david-seddon.com

Radar Duga-1

Picking up the action from last time, we finished off our lunch (or snacks for me) and headed back to the bus.

We toured the area around the former Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, which in all honesty wasn’t all that fantastic. It just looked like an industrial zone, and if you didn’t know any better you wouldn’t have been able to say you were anywhere of note. Even the radiation wasn’t as high as we’d seen elsewhere.

The Arch, or Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, is certainly something to see. I didn’t take any photos of it - apparently the police are very demanding of what angles are OK and what aren’t, so I thought I’d play it safe. It’s a massive structure, some 90 metres high and 150 long. So far the cost is thought to be in the region of 1.5 billion Euro, an eye-watering amount.

In the aftermath of the accident, it was decided that a structure needed to be built over the damaged reactor, to stop more radiation leaking out. The initial aim was to get something in place as soon as possible, and this structure was called the Sarcophagus. Taking just 5 months to build, this was certainly achieved.

What they didn’t get was longevity. It was estimated to last just 30 years, but even before that cracks started appearing, and if there’s one building in the world you need to stay intact, it was this one. The Arch is designed to entirely cover the Sarcophagus, and, once complete, use robots to dismantle the Sarchopagus and remove the radioactive material.

I certainly hope this one holds out. Apparently it has a warranty of 100 years, and goodness knows what they’ll do if this one wears out. You can’t keep building bigger and bigger containing structures, after all.

We took the inevitable and tiresome group photo in front of the Arch. I don’t know why on every tour we have to have a group photo. I never know where to look and it’s always awkward. You can’t really ask not to be in it either without being that awkward guy. Mercifully I haven’t got my copy via e-mail yet, and hopefully the radiation destroyed the picture.

Rejoining the bus - it was beginning to feel like home - we headed off to one of the final stops, the formerly top secret base of Radar Duga-1 (also known as Chernobyl 2, designed to confuse enemy spies who were presumably not very bright if so confused).

The poor attempts at subterfuge continued with a somewhat childish bus stop. This looked very out of place, and our guide explained to us that the Soviets had marked the base as an abandoned holiday camp for children on the map. The thinking was that an enemy spy, out for a drive, would see the abandoned holiday camp marked on the map, see the childish bus stop, and elect to not investigate further. I can’t imagine what sort of intelligence services would be fooled by such a ruse.

Anyway, it didn’t matter after the disaster. We trundled along to the base, where we were met by a stray dog that our guide introduced to us as Tarzan. We’d previously been warned not to touch the stray dogs too much, as they could go anywhere and carry radioactive dust around with them in their fur, but Tarzan obviously knew our guide and kept jumping up at her. He followed us all around, and in a way it was nice to have an animal guide trotting ahead of us. As long as you put the radioactive dust out of your mind, that is.

After a short walk, we came across one of the stranges sights I’ve ever seen. It was a massive radar reciever built by the Soviets as a “over the horizon” radar. I won’t go in to detail, but apparently at the time radar had a limited range and couldn’t detect things over the horizon, due to the curvature of the Earth. This is not ideal if you’re the Soviet Union trying to see what the United States are up to.

So, those cunning scientists came up with a way of doing it. I’m not a radar technician, I don’t know the science of how it all works (by all accounts, not very well). Apparently it was used to determine that a different early missile warning system the Soviets had had produced a false alarm in 1983, so I will give it some credit for that.

There are many rumours about this radar. Some say that the Soviets built it to send waves that cause depression towards the United States. Another is that it is designed to induce natural disasters like earthquakes. I’m not sure about these. From what I’ve learned about the Soviet Union, if they had a machine capable of doing anything like this there would be propaganda dedicated to it and the triumph of Soviet Power.

It is a massive structure. You stand at the base of it and move your head back to try and see the top and end up nearly falling over backwards. It’s lengthy too, and took us some time to get to the end of, Tarzan coming along with us.

For some reason it was here that the strangeness of the place really struck me. If, just a generation ago, I’d been teleported here I would have been shot on the spot for a British spy and yet here I was, walking through a snowy forest alongside what was top of the line, classified, military technology.

Reaching the end, our guide asked us if we wanted to go back to the bus or take the long route, taking in some creepy buildings. I jumped on the creepy buildings plan.

The first room was certainly creepy. It was a tunnel running the length of the facility, obviously now in darkness. We had to watch the ground for holes that went through to the cooling facilities, so I paid close attention to my footsteps. I’m not much of a computer gamer these days, but it could have been from any number of them. I kept expecting things to leap out at me, and it was only afterwards that I realised I could have used my phone as a torch.

Exiting the tunnel, we came to a forest which had electronic equipment strewn all over the place. This stuff wasn’t looted, it was just thrown out by the liquidators.

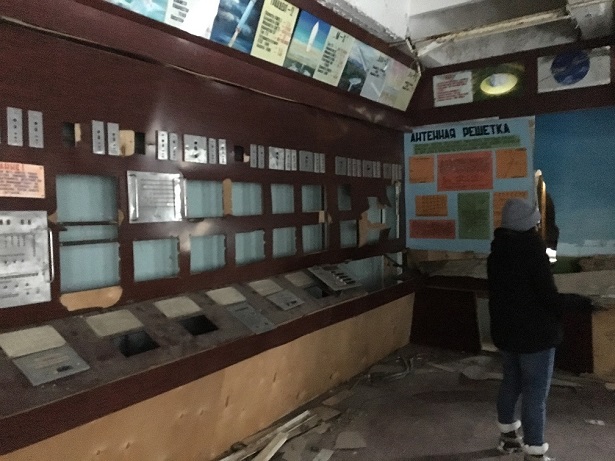

We then went in to one of my favourite rooms. This was a room where the controllers of the radar equipment were taught about different things. Against one wall was an almost cartoon-like display showing how the radar works by bouncing beams off the atmosphere. Above terminals there were signs providing information about the various types of missiles NATO had and their ranges and speeds and so on. Everywhere there were electical schematics. It was just incredible.

From here we went to another room, this time an old server room. Some of the equipment outside was from here, and again it was lifted straight from a computer game. Holes in the floor, empty racks, dark, dark corners and smashed windows. It was really spooky.

That was about the end of our time at Duga-1. It was a shame to go, I could have stayed for much longer, prowling through the rooms and seeing what went on. We also had to say goodbye to Tarzan, which was a bit sad because he was all on his own out there. Our guide had said that during the winter there are fewer people around and that’s why he was hanging around with us. It must get very lonely for him out there.

The last few stops were short but moving. We saw the memorial made by firemen to those who were first to respond to the disaster, many of who died. We also saw some of the robots used to clear some of the debris away. I’m not a massive fan of robots, and some of these looked like toys. Still, if they helped even a little I suppose I’ll forgive them.

And that was about it for my tour. It was an amazing experience, one of the greatest things I’ve ever done. It’s sad that such tragedy spawned so many amazing sights though. There are no known numbers of how many people died or became seriously ill after the explosion. Some estimates are comically low, some astronomical, but I think it speaks volumes that Valery Legasov, the chief comissioner of the report into the aftermath of the disaster, committed suicide.

It’s interesting to see though, particularly in the current political climate with various world leaders who should know better using nuclear weapons as positioning tools. I was at the scene of an accident and the damage was horrific - I can’t imagine how devastating it would be if it were weaponised. Ukraine and neighbouring Belarus have suffered greatly from this, in lives lost, sickness, and the cost of cleanup.

Let’s all just put the scary nuclear devices down, yeah? Really, we don’t need more disaster zones. Written on February 17th, 2018 by David Seddon